News Story

Ollie Dook is one of six artist filmmakers who have been on The FLAMIN Fellowship in 2020-2021, FLAMIN's year-long programme offering development funding, mentoring and support to early-career moving image artists. Ollie's work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally at various venues including Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh; Hannah Barry Gallery, London; Humber Street Gallery, Hull; NADA, Miami with Daata Editions and Zabludowicz Collection, London.

We caught up with Ollie to talk about his work with 2D and 3D animation, the emotional history of Jumbo the elephant and his recent explorations into the relationship between memory, technology and mental health. He also gave his account of being on The FLAMIN Fellowship, and offered some useful advice to those planning to apply.

Portrait of Ollie Dook. Photo by Brynley Davies. Courtesy of the artist

Video: interview with Ollie Dook

A full transcript of the video interview is available to download here.

FLAMIN in conversation with Ollie Dook

FLAMIN: Could you tell us about your practice?

Ollie Dook: My practice is really an attempt to decode an ongoing relationship with images, one that spans through history and into the contemporary age, and really what that relationship says about the human condition. My work will take form, therefore, through a process of mining images as somewhat cultural artefacts. Once I’ve mined these items, I will then re-articulate them within my own processes, which often include digital reproductions in 2D animation or 2D stills, both in digital or in print, but also largely in CGI. These reformulated images then populate my idiosyncratic world in order to create links between things that would otherwise seem disconnected, in order to highlight an idea that was pushed onto me through absorbing those images in the first place.

So throughout my work, there's really a common thread, which is the process in which I deal with this material. But then in specific works, I often will focus on more specific themes. So a lot of my work in the last few years has really focused on the human-animal relationship, or the real, truthful and false through ideas of conspiracy. Most recently, I'm looking into the theme of memory and how that relationship to memory is something that's often mediated through images, and the technology in which those images are produced on and stored within.

Ollie Dook, Reflections on a Visit V2 (2017), installation view at Hannah Barry, London. Courtesy of the artist

Ollie Dook, Animal Stories (2018), video still. Courtesy of the artist

How do audiences interact with your moving image work?

One consistent thing with some of my previous work is that it has often found its resolution in the form of an installation within a gallery context. I’m most interested in attempting to echo the ideas present in a film within the experience of the audience and the space they’re viewing it in. One project where I pushed this notion to the nth degree was my show Of Landscape Immersion at Jupiter Artland in 2018. Within this work, I was forced to produce a new work in an outdoor landscape, which, when working in video and moving image provokes a certain kind of problem, I guess. So in an attempt to resolve this problem, I cut up the interior of two shipping containers, and divided the space with two-way mirrors and lighting, which forced the viewer when watching the film (which was also projected on a two-way mirror) to at moments have their reflection embodied within the screen. Viewers had their presence made visible to those entering the space, who were then forced to watch them before watching the video.

Second to that, I have also worked with more single-screen work. My project Animal Stories for Daata Editions was built for the single screen and it was an online commission, and part of that meant I was forced to make it work in an episodic format. So within that I created more traditional animations that worked in reference to the early Disney cartoons - without language but using music and a moral metaphor at each episode’s core.

My latest work I did for Humber Street gallery in Hull, a project called Proboscidea Rappings, which was an attempt to recall the life of the elephant Jumbo. This was a project where I tried to embody a sculptural presentation, both in the way the film was displayed on a vertical screen that matched the height of the elephant, but also in the way it was surrounded by these faux elephant skin sound insulation panels, each of which was recalling a moment within Jumbo’s history. This film was almost purely made in CGI and relied heavily on the animation of a CGI model. In many ways these models can be viewed as sort of 'dead puppets', but I was inhabiting that with emotion in order to provide a space to give a retelling of that history from the elephant's perspective, as opposed to the story that was so often mediated through a human lens.

Ollie Dook, Of Landscape Immersion (2018), installation view at Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh. Courtesy of the artist

Ollie Dook, Of Landscape Immersion (2018), video still. Courtesy of the artist

Could you tell us about the project you’ve been developing on The FLAMIN Fellowship?

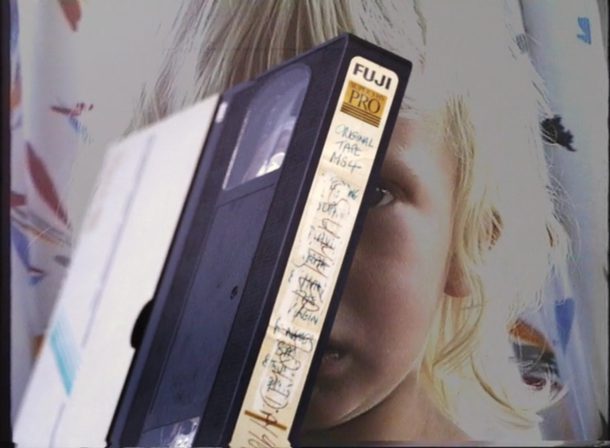

The project I applied to FLAMIN with is something I've been thinking about for a long time actually. It's a project that is hoping to explore our relationship to memory, and specifically how that relationship is informed or mediated through a certain type of image or technology. This project was something that I began thinking about in response to my dad's condition of Dementia, which was something developing in the last five to ten years really. So, over a period of time, I began to think slightly differently about the way in which I related to memory and the way others related to memory. And it was around this time that I discovered an archive of S-VHS tapes, which was somewhat precariously stored somewhere in the family house. I began thinking about how these tapes were slowly eroding with time and I had this urge to preserve these tapes, much in the way I would have an urge to preserve my dad's memory. And this was the spark that blossomed into this more conceptual work about how we deal with memory, and specifically the loss of memory.

So for this project, I've had to really introspectively look both at my own memories and histories, but also my family's histories. That's required me to interact with my family members and really has forced me to try to preserve those memories by recording conversations with them. So this process of not only just taking imagery that already exists, but trying to kind of tease it out through conversation and interaction, is a slightly different and new way of working for me personally.

How does your work with sound relate to this current project?

Music and sound have become more and more of an important part of the work. Both thematically, in terms of how music and memory have this inseparable relationship that is so important, but also in the way in which care is operated to people in my dad's condition. Sound is also just really deeply entwined with memories emotionally and I'm currently thinking a lot about how a song can bring back a moment in the past. But it's not simply just the remembering of that song - it's about how it opens up the portal to those other memories. Whether it's the moment of being inside your living room, or the moment you went to see a concert, it provokes all of these other moments in time and those other moments of time are also associated with sounds, whether it's voices, or the opening of a door, or the creak of a particular chest of drawers or something. Those sounds really embed themselves within the brain and often act as portals to memory. So I'm experimenting currently with not only embedding musical compositions, but also sound design moments of inconsequential sounds to provoke that same sort of feeling.

But I do find with music as well, it's quite refreshing because it's always a step back to a moment of naivety. I'm not so well versed in the technicalities of music, and therefore I'm able to experiment without knowing the rights and wrongs of everything. Whereas with video production, I'm so technically well-versed now that there's not that level of surprise, whereas music often sort of provides that for me, which is lovely. Whilst I did music when I was much younger, it wasn’t really until I was in my last year of university that I began making a video piece that included sound, and suddenly it became this more meaningful part of the work, and actually often its something people would pick up on more than the visuals. And so that relationship has been developing ever since, really.

Ollie Dook, Summer Holday /96 (2021), video still. Courtesy of the artist

Ollie Dook, Memory Tape for Dad (2021), video still. Courtesy of the artist

Where does your recurring interest in technology come from?

A lot of my work takes place within the realm of the computer, working in both 2D and 3D animation, and often working with found digital video and the editing process of this digital material. One of the things that has developed within this project is realising that the interest is not so much dependent on ultra-modern technology as it is with just technology in general. I think there's a certain concern within my work that really relates to how we interact with technology and how technology can expose something about us, but also the way we interact with it really says a lot about the things that we're trying to do with it. I’m also interested in the things it kind of hides and reveals, throughout history.

Your recent work increasingly uses narrative and storytelling, how did this come about?

I think my interest in storytelling really grew out of my project Proboscidea Rappings, where I was looking at the life of Jumbo the elephant, because that had a clear narrative arc. And in fact, what was so interesting about Jumbo as an entity was the fact that he had had this narrative created for him by the way in which he was viewed by humans. So story became very intrinsic to the ideas and therefore I tried to deploy the work with a sense of narrative. That really made me interested in narrative more and actually just becoming more interested in film, rather than, say, artwork in the traditional sense.

The project I’m working on at the moment obviously has the tough problem of trying to create a narrative of one's own life. And that's hard, not only because it's deeply personal and somewhat painful and difficult to distinguish, but also just because you really are aware of so much happening, but it's quite hard to distill the important moments into a narrative that can be conveyed in a way that becomes meaningful to someone else, outside of myself and outside of the family. So meeting with screenwriter Ellis Freeman through the Fellowship has been a really good way of working out a way to develop language. He’d make me ask myself questions about the tone of the film, what the language is there to do and how to convey a story that is meaningful as well as structurally coherent. He also got me thinking about what the voice of the story is, and how you get through to people on that more emotional level. I feel like in the art world, people's work is often more aiming towards a more academic or ideas-based conclusion, and tends to avoid the emotional, whereas film often utilises emotion throughout popular film or arthouse film.

Ollie Dook, Proboscidea Rappings (2019), installation view at Humber Street Gallery, Hull. Photo by Jules Lister. Courtesy of the artist

Ollie Dook, Proboscidea Rappings (2019), installation view at Humber Street Gallery, Hull. Photo by Jules Lister. Courtesy of the artist

Ollie Dook, Proboscidea Rappings (2019), installation view at Humber Street Gallery, Hull. Photo by Jules Lister. Courtesy of the artist

What was your experience of being on The FLAMIN Fellowship?

I think the FLAMIN Fellowship has been a really great way to enable a more personal development within my own work. It's been a way to move on to scarier topics within my own work - work that I was probably more nervous to make and not necessarily going to get such support to make through other avenues. So having a year to slowly develop those ideas with a network of artists and people with a lot of experience, building those connections and refining that idea has been immensely beneficial to me on a more personal development level.

What career stage were you at when you applied to The FLAMIN Fellowship?

When I applied to the FLAMIN Fellowship I had had a couple of years out from my Masters degree at RCA (Royal College of Art, London). In those few years, I feel quite lucky with the amount of opportunities I'd had. I had exhibited in art fairs, in commercial galleries, and had commissioned opportunities to present my work solo as well as in group shows. But I think, for me, that time was quite quick and I was very much wanting to take the next step to develop my work beyond perhaps a more tight-knit theme, and stretch it over into a broader concern that will help me see through my work in the years to come, I guess. So in that sense, I still feel relatively young as an artist and very much in need of time in development.

Do you have any advice for people applying to the FLAMIN Fellowship?

I think writing about one's ideas, through the process of applications and through statements or whatever it may be, is an incredibly hard thing to do. I personally find it quite hard, probably partly due to my own lack of writing ability in terms of dyslexia or whatever it might be, but I think there's a tendency to want to overcomplicate ideas in the written form. That's something I think that is more pushed in the art world or art education. But from my experience, talking to others that are slightly more removed from that, often a more simple approach and a more clear and simplified way of talking is often an easier way to convey an idea. I do think practice is, unfortunately, one way to just simply get better, and I do think over time, my applications have become more concise due to the simple process of doing them over and over again. It's good just to speak somewhat honestly and simply. Actually, that might make things a lot clearer. In art school, people are forced into a way of talking, which really overcomplicates for the sake of complication really, and doesn't really serve to convey the idea, but more confuse it.

Ollie Dook, Animal Stories (2018), video still. Courtesy of the artist

Ollie Dook, Smashing Windows (2016), video still. Courtesy of the artist

What are your ambitions for the near future?

I do want to pursue a certain high level of ambition within the filmmaking. I think being part of the FLAMIN Fellowship has helped me get a better insight into the more film side of artists' moving image as opposed to the more artist's world. Within that film world, you do become aware of the scope - how much work goes into it, and the scale of things that might need to extend to get to a certain point. So for me, over the last couple of projects, a lot of my focus has really developed into the idea of narratives and how we as individuals create narratives within our lives. And stories in general have become more of an important focus for me. So in the future, I would love to further pursue that and develop the filmmaking in order to tap into that storytelling, filmic language.

Website: www.olliedook.com

Instagram: @olliedook