News Story

Julia Parks is one of six artist filmmakers who have been on The FLAMIN Fellowship in 2020-2021, FLAMIN's year-long programme offering development funding, mentoring and support to early-career moving image artists. Julia’s practice encompasses film, sound and photography, which she uses to explore the different relationships between landscape, place and people, often focusing on the west-coast of Cumbria where she is based. A graduate of Central Saint Martin’s School of Art, Julia has exhibited work in exhibitions and film festivals in the UK, Europe and Japan, as well as being featured on BBC’s Countryfile.

We spoke to Julia about her work, how she finds and uses archive film, documenting the idiosyncrasies of rural life, and her advice to artists planning to apply to The FLAMIN Fellowship.

Portrait of Julia Parks. Photo by Elizabeth Carr

Video: interview with Julia Parks

A full transcript of the video interview is available to download here.

FLAMIN in conversation with Julia Parks

FLAMIN: Could you tell us a bit about your artistic practice?

Julia Parks: I would call myself an interdisciplinary artist, because I make work across a range of media - photography, sculpture, installation - but I primarily work with moving image, using 16mm film and archive footage. My work for the past five years or so has really focused on the area where I live, in West Cumbria, exploring the way in which the industry and work that people have done has really shaped the landscape. To give you an example, I’ve lived close to these white cliffs all my life which you would think they were natural cliffs, but it wasn’t until I was researching the area to make my film Workington Red that I found out from people's stories that they were all man-made, built from the steelworks and ironworks. They were the slag banks that had been in the town when it was a hub of heavy industry. I think that's a really good example of the kind of area that I'm interested in - talking to people and finding out about the place in which we both live and discovering all of these histories that aren’t marked on maps, that aren’t there anymore. For me it’s about unearthing all of these hints, these left-overs to that history, and thinking about the impact they have on us today.

How do you go about making your work and where do you show it?

Up until quite recently I’ve mainly worked on my own - shooting, editing, doing the sound. But in the past couple of years I’ve started working with an editor and a sound designer. I’m really interested in sound, so I’ve been collaborating with Heather Andrews, a sound artist, on my latest works. I’ve also been working with Jameela Khan who will be producing my next film. But I think it’s important that its me behind the camera, doing the interviews, and getting to know the people and their stories.

Often I’m showing my works in the context in which they were made - so in old buildings or an iron mine that had been converted into an art centre. I’m really interested in being able to show work in those contexts, because the place speaks directly to the work in some ways.

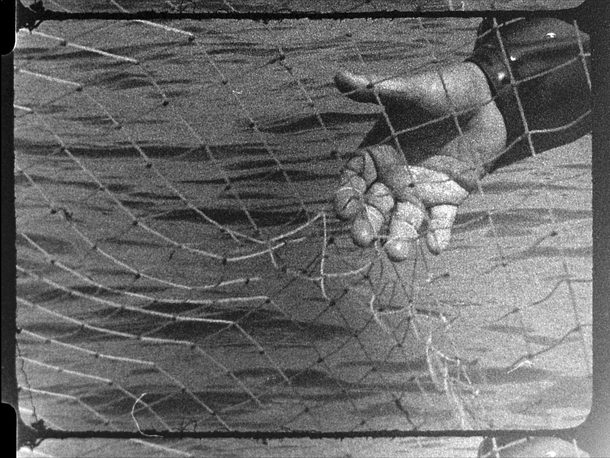

Recently I made a film called HAAF with some local fishermen, about a centuries-old fishing technique used by Vikings, which is now only practiced in a couple of places in the UK including on the Solway Firth close to where I live. Because of the COVID-19 lockdown I was able to screen the film online, and broadcast a conversation with the two fishermen who feature in the film. This was really interesting because we normally wouldn’t get the opportunity to have that first hand experience and history so accessible.

Julia Parks, Workington Red (2019), film still. Courtesy of the artist

Julia Parks and Heather Andrews, HAAF (2020) film still. Courtesy of the artists

Can you tell us about the project you applied to The FLAMIN Fellowship with?

The project I applied with was specifically exploring the way in which seaweed had been used historically, now and also into the future. Seaweed is a subject that I'd been looking at and researching for some time. I'd made a short film using seaweed as a material to actually develop a black and white image. I became really interested in the idea of using seaweed within the context of the Irish Sea, thinking about the nuclear power station, Sellafield, and how the remnants of the activity that took place there would have been in my developed image. It began with that material exploration, but as I delved deeper so much to uncover and the project grew in scale and ambition. Part of the reason I wanted to do The FLAMIN Fellowship was to really try and narrow down some of these subject areas – to look at seaweed, not just within the Cumbrian context, but within a wider UK context. So it's a much larger subject than anything I'd really taken on before.

Why is seaweed important?

Well, for me, seaweed is a really interesting material. It's between land and sea, and it's constantly oscillating between the two as the tides come in and out. It's got this kind of incredible history of being a resource, but also has all of these stories connected with it, like the folklore of it being something dangerous and pulling people into the sea, whilst also being a life giver in it uses in health and medicine.

There's a long history of trying to commodify seaweed. And now it's being looked at again, I'm really following debates currently going on in Norway, Scotland and in Bantry Bay in Ireland too, which has seen lots of protests about a type of seaweed trawling. This large scale harvesting of seaweed has provoked controversy because these kelp beds support massive amounts of life and biodiversity. This is the next debate – what will happen to these massive northern kelp beds in the decades to come? I'm really interested in that relationship between using material and then when that use starts to put that material under threat. There are also many people trying to set up more sustainable farms where seaweed is grown on ropes as opposed to taken from the wild.

Julia Parks, film still from test footage, 2021. Courtesy of the artist

Julia Parks, BBC Bladderwrack. Film still developed in seaweed. Courtesy of the artist

Has being on The FLAMIN Fellowship effected your work?

Being on The FLAMIN Fellowship has made a big difference to my work. I think when I started the fellowship, I was really wedded to this idea of making a film developed in seaweed, and that the materiality of that process is what it was going to be about. But actually, since starting the Fellowship, I've become much more interested in the stories connected with seaweed and the way they are explored. The voices I’ve been exposed to throughout the programme, and the feedback I’ve had from my peers has opened me out to all of these other ideas and these different ways of approaching it. So I think it has changed me, and I've taken a much more planned approach, for example in the way in which I use archive footage. Before I would have wouldn't have really known all of the places to look, but from the advice I’ve received from artists and institutions who’ve spoken on the Fellowship’s workshop programme, I've really been looking at new places that I could explore archive footage and sound, and oral histories as well.

What audiences do you want to reach with your work?

The most important audience for me, to start with, is the local audience close to where I live in Cumbria. Often I feel that I've been making work with this in mind, whereas this seaweed film is reaching a further than that. I'm hoping to make it up in Scotland, so that would open up a big audience of local people who live in that area. But I'm also hoping the environmental themes within this work will also have wider interest for art audiences, as well as those who are interested in the environment, within the UK and broader. I'm interested in introducing people who might not know much about seaweed to the subject and showing some of the interesting historical links, and its potential uses in the future.

Julia Parks, The Girl Who Forgets How to Walk (2020), film still. Courtesy of the artist

Julia Parks, Solway Steel and Cyclamen (2019), film still. Courtesy of the artist

Why did you apply to The FLAMIN Fellowship?

I am connected to various artists in Cumbria, but my work is quite specific in the way it explores documentary themes. And I felt like the FLAMIN Fellowship opportunity would be interesting at this point in my career, because I just made some work that I felt had moved my practice on. But it's having input from others that I was kind of really yearning for. And I think that's why I felt like “yeah, I will go for it and put in an application”.

What advice would you give to people applying to The FLAMIN Fellowship?

I wasn't really sure whether to apply and I was quite late in applying because I thought I was unlikely to get onto the programme because I thought there’d be so many people applying. I've got this massive folder of things that I've applied for in the past, and it's rare that you get these opportunities, but I did decide to apply and I was successful. So my advice would be to take the opportunity, and to put your name forward for this opportunity, because I’m really glad that I did.

For me, the idea I applied with I'd had for a very long time, so when I was writing the application in some ways it was quite easy, because I'd had this idea for ages. I'd already put it forward in other contexts, but not necessarily been successful. So the idea was there, which helped. But I did also spend a long time looking through the guidelines. And I listened to the How to Apply video that had been made, and was really checking that I was feeding back in the right way to the questions that were being asked. I would say I probably spent a day or so putting it together, but also thinking time before that.

What are your hopes and ambitions for the future?

For me, the key thing is to continue to make films I’m proud of, but its also about making films about where I live. I think the driving force behind that is because there’s so little I can find about this area of the UK. The films just aren’t there in the collections and archives. I have this idea that if in 50 years time there’s someone who is, like me, really interested in archives, they can then find some of the work that’s been made about the area. It’s important for me to bear witness to what’s happening here and have an element of social documentary to what I do.

Julia Parks, Solway Steel and Cyclamen (2019), film still. Courtesy of the artist

Julia Parks portrait with Bolex camera. Photo by Jameela Khan

Website: www.juliaparks.co.uk

Instagram: @juliaemilyparks