News Story

Anita Safowaa is one of six artist filmmakers who have been on The FLAMIN Fellowship in 2020-2021, FLAMIN's year-long programme offering development funding, mentoring and support to early-career moving image artists. Anita’s work has been screened as part of the BBC New Creatives initiative at the ICA, London, London Short Film Festival and Aesthetica Film Festival, York.

We spoke with Anita about her work across different art forms including filmmaking, archive, writing and VR, and about her new project exploring the experiences of Ghanaian migrants moving to London in the 1980s and 90s.

Portrait of Anita Safowaa. Courtesy of the artist

Video: interview with Anita Safowaa

A full transcript of the video interview is available to download here.

FLAMIN in conversation with Anita Safowaa

FLAMIN: Could you tell us about your practice?

Anita Safowaa: My artistic practice takes quite an interdisciplinary approach and its main focus is to explore under-documented cultural moments and subcultures with the purpose of preserving them, and to reimagine these moments using a range of media, including moving image, personal archives, reflective writing, and also VR. At the moment, a lot of my work really focuses on understanding the layers that go into black British identity in order to arouse discussions and notions around Britishness, but also, my work aims to create an intimate and immersive learning environment.

Using archives in my work has been foundational since my first short film, A Single Bracelet Does Not Jingle, which I made as part of Stop Play Record. This work was very much focused on understanding the British-Ghanaian identity and understanding how two cultures can be embedded into one. For this I shot new footage, but used sounds from home videos that I had and conversations I had recorded in order to create the set design in the actual short film. From doing that I understood the importance of archives in my practice in terms of being a portal to memories and as a way to evidence life. I took that archival practice forward when creating my VR piece To Those Before Me which I did for the BBC New Creatives. Although I had a musical score created for this work, I also included archival sound from my first trip, when I actually went back to Ghana when I was I think about 14. So I had recordings of sounds from the markets and the hustle and bustle of Kumasi, and included that in the piece as well. So it was very much about creating an element of the past but also making it relevant.

How did you get started working with VR?

I was fortunate enough to be on the BBC New Creatives programme, where I was partnered with SPACE gallery. At the time that I pitching this VR piece I didn't actually know how VR technology worked, but I knew after doing an experimental short film that I really wanted to explore the idea of making my work more immersive and more experiential. The commission programme allowed me the space to understand VR through being with VR cinematographers and being linked up with a VR producer, who really gave me insight in terms of how to think about VR when you approach it for film. For instance, the camera doesn't move in VR, so they got me thinking about how else I can direct or influence the gaze of the viewer or the participant. They also gave me great platforms that I could use to improve my VR literacy, but it was mainly through on the job learning and being hands-on to experience first-hand how the VR cameras worked, that I was able to learn the medium. I think that's pretty much the same kind of approach that I take with any new medium that I use. It's very much about just grabbing it, experimenting and trying to figure out how it works. And then from there, I kind of reverse-engineer and look at the actual back end and how you're supposed to actually be using things to kind of merge everything together.

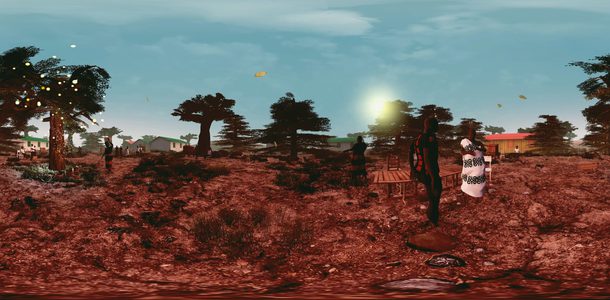

Anita Safowaa, To Those Before Me (2020), installation view at ICA, London. Courtesy of the artist

Anita Safowaa, To Those Before Me (2020), film still. Courtesy of the artist

Could you tell us about the project you’ve been developing on The FLAMIN Fellowship?

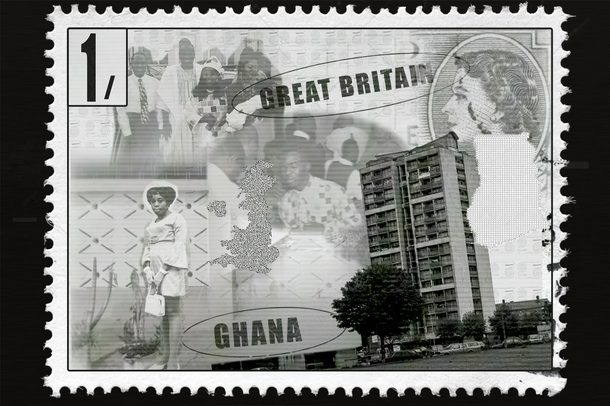

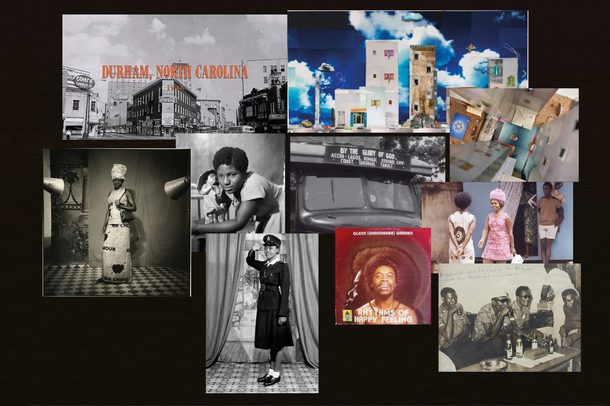

So I applied to the FLAMIN Fellowship programme with an idea of wanting to explore migration and trying to understand what that meant in the context of the UK. And through the process, I came up with A Journey To Stillness, which is a multi-screen installation that explores the migration experience, but outside of conflict and understanding what other influences there are on migration. For this project, I'll be using Ghanaian migrants who moved to London during the 1980s and 90s, as a case study to really understand why they moved from Ghana to the UK, but also understanding the nuances surrounding assimilating within a new society and understanding what their expectations were versus the actual reality. The stories I'm hoping to bring to light through this work are very much embedded in collective memory, because I'm interviewing different Ghanaian elders and going through different archives to gather what life was like. So multi-screen installation very much lends itself to that but also gives this sense of togetherness that I really want to bring through my work.

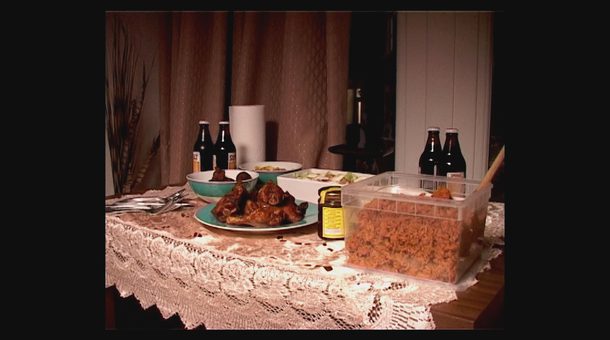

Anita Safowaa, A Journey to Stillness, production image

Anita Safowaa, A Journey to Stillness, research moodboard

What was your experience of being on The FLAMIN Fellowship?

Being on the Fellowship programme has really changed the way that I approach my artistic practice. Before, I wasn't really prioritising it as much as I am now, finding space and time for my work. Now I have more of an idea and intention about what I'm doing and what I'm going for, and I'm trying to prioritise my practice above other things and keep this momentum I’ve gained from being on the programme. Keeping up a job whilst being an artist can sometimes feel like I'm sacrificing too much time for other people or businesses, so I'm really thinking about what am I going to do for me now.

Being on the programme and speaking to other artists that are more mid-career or further along in their career than I am, but also speaking to artists that are on the same level as I am, there was this opportunity to knowledge share, and understand how other artists are approaching their practice and things that I can take on board. But also, it's given me the confidence to really understand my position in this world, in terms of what my practice is contributing and also having more confidence in talking about my practice. It’s really given me insight in terms of how I could continue pushing it forward and finding out what fuels me. I think I've been one of the fortunate ones in that I was able to do this programme. It's given me a lot of time to think and develop, and actually, I guess, take the plunge and figure out what I want from life.

Do you have any advice for people applying to the FLAMIN Fellowship?

My top tip for applying for The FLAMIN Fellowship programme - its going to sound very basic, but it was very hard for me to do at the beginning - is to just apply. I know that sounds very basic and straightforward, but oftentimes as artists or creative practitioners, we’re always questioning our work or questioning whether we’re ready for certain programmes or opportunities. But essentially, you'll never know until you actually apply. So that would be my tip - overcome that hurdle of self-doubt, just get an application in and see what happens.

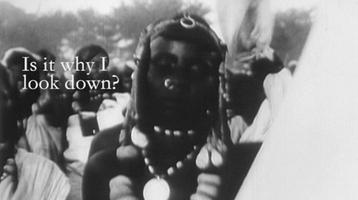

Anita Safowaa, A Single Bracelet Does Not Jingle (2018), film still. Courtesy of the artist and Stop Play Record

Anita Safowaa, A Single Bracelet Does Not Jingle (2018), film still. Courtesy of the artist and Stop Play Record

How did you get into artists’ moving image?

I suppose my journey into artists' moving image is quite unconventional. I actually didn't go to art school, and my art training stopped at A level. At the time when I was thinking about what university to go to after being in sixth form, the University fees were going up in the UK, so I tried to do 'the smart thing' and I went and did a fashion business course at the London College of Fashion. Doing that course I understood the business side of fashion, but what really interested me about that course was the cultural and psychological elements of fashion, and understanding why people do what they do. In the third year of doing that course, I missed having a creative outlet in order to explore these ideas that I was coming up with and I really wanted to kind of go down a fine art route. I thought about doing an MA in fine art, but realised I didn't have the finance in order to do that, so I began thinking about what was accessible to me, and what could I kind of leverage.

I guess where my art practice started was photography, because photos are instrumental in the house I grew up in. My mom isn't a trained photographer, but she always used to take pictures of us and we have mountains and mountains of photo albums. When people come to my house, they're always saying it's like a museum because we have so many photos and ornaments. So I started exploring my ideas through that medium and writing what I was feeling in relation to what I was seeing around me. It was at a time where my area was being regenerated and the landscape started to change. So I started talking to people from my area about it and documenting the area through taking pictures and writing about things that used to be in there and reflecting on that.

From there, I took an interest in filming and understanding the possibilities of a camera, but also looking into experimental filmmaking, and I went to Kingston University to study filmmaking. I remember I chose that course because they did both digital and analogue camera training, and it was very much embedded in humanities and a sociological kind of study and approach to film. I think that's where it kicked off for me in terms of really understanding what it is that I'm interested in and thinking about ways that I can explore it in a non-conventional manner.

Anita Safowaa, A Single Bracelet Does Not Jingle (2018), film still. Courtesy of the artist

Jenn Nkiru, BLACK TO TECHNO (2019), video still. Courtesy of the artist

Are there any particular influences on your practice?

When I first saw Jenn Nkiru's work, it changed how I think about moving image and what is considered a film. Before then I'd never really seen anyone's work that had the approach that she had, in terms of having a mix of shot footage, interviews and dance, it was very multi-dimensional. When I saw it as a two-screen installation at 180 The Strand in London, I felt totally immersed in her work. I admire how her work really embodies the subject that she's exploring. Her film BLACK TO TECHNO is a big inspiration for me, mainly because the work itself really embodies the energy of Detroit house music whilst visually incorporating the art of DJing in the editing style. In my own work, I get a lot of inspiration from music, both through the rhythms and understanding the context that influenced the song or genre. So I think that's why Jenn’s work directly speaks to me.

What are your ambitions for the future?

I hope that in the future I can really extend my artistic practice to collaborate with other artistic disciplines, whether it be musicians, DJs or creatives. I really want to extend this notion of experiential storytelling that is grounded in archives and oral histories, to really bring forth an enjoyable, different and alternative kind of art experience, and one that is more inclusive and not restrictive in terms of who can visit.

Website: www.anitasafowaa.co.uk

Instagram: @anita_safowaa