It helps to think together: On Rosalind Nashashibi’s The Invisible Worm

The Film London Jarman Award 2024Emily LaBarge

Rosalind Nashashibi, The Invisible Worm (2024), film still. Cinematography by Emma Dalesman and Rosalind Nashashibi

You can’t know what it is, not really, the so-called invisible worm. Not in William Blake’s poem ‘The Sick Rose’, nor its illustrated plate in Songs of Experience (1794). In the drawing that accompanies Blake’s short and famously enigmatic poem about a diseased flower beset by an ‘invisible worm / That flies in the night / In the howling storm’, thorny branches with yellowed leaves curl around the eight-line text written in sinuous amber script. The thwarted bloom of the poem’s title lies red and heavy at the base of the image and a long white grub (very much not invisible) luxuriates in its petals; its head raised with an unmistakeable face that bears an expression of victorious delight. But the visible worm, with its lugubrious visage, is not the invisible worm.

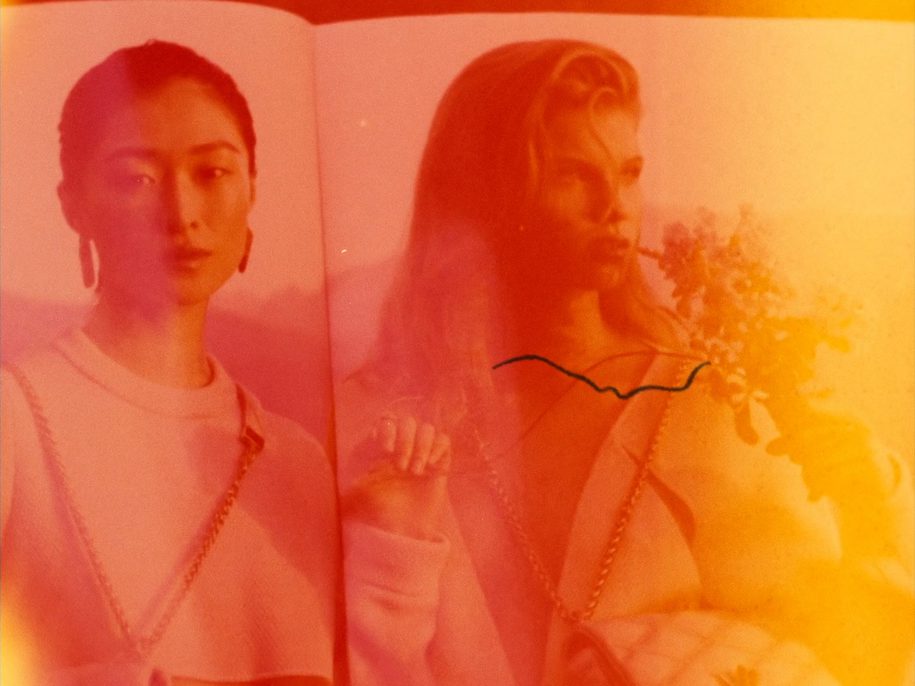

In Rosalind Nashashibi’s film The Invisible Worm (2024), we might think we see the titular larvae in its closing minutes as a ‘hair in the gate’ – the filmic term for a piece of debris that gets stuck to the film gate and thereafter appears as a fixed dark line hovering over the otherwise moving image. About 12 minutes in, a small wiggle of a line flickers quickly over the forehead of a dark-haired model (the actress Margaret Qualley posing for a Chanel jewellery campaign) in the open pages of a glossy magazine. Like a stray strand of curly mane, it is almost imperceptible until the camera moves down onto another slick ad (blonde Gigi Hadid looking bored for Miu Miu) over which the dark worm stands out crisply against white and then purple, and then begins to move, squiggle, wriggle, inch, squirm, as if the camera lens is a petri dish that holds a living experiment.

And it does. It contains art, friendship, politics, fashion, projection, fantasy, economy, as one of three women who shift in and out of scenes at the centre of the film repeats. ‘Economy…economy’, she says, a word that can mean the interconnected structures of capitalism, but also thrift, spareness, exactitude. ‘Economy’, she says, sitting at a candlelit bar, and trails off, before reciting Blake’s poem in solemn tones as we see more magazine spreads of beautiful faces and luxury goods and the ‘Elegy’ of Benjamin Britten’s 1943 song cycle, Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, rises and swells in the background. A tenor’s voice, high and sweet, arcs through the lines of the poem – ‘Oh rose, thou art sick…’ – and the slender black line, animated and agile, traverses the celluloid surface as the British Houses of Parliament as seen from the river passes by in the sun. Home of the rotting Albion rose of the day, will these buildings provide a feast for this accident of film, this now visible worm? Or is it a quiet interloper that only the viewer can apprehend, waiting to infiltrate and observe from within?

Rosalind Nashashibi, The Invisible Worm (2024), film still. Cinematography by Emma Dalesman and Rosalind Nashashibi

Some scholars have thought of ‘the invisible worm’ as a reference to the historical ‘wild worm’ or the ‘notturne larva’, invisible spirits mentioned by St. Augustine in his 5th century The City of God, which later became part of Middle Ages and Renaissance demonic lore.1 For the 14th century Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio, these invisible worms were created by the deity of dreams, Morpheus, to invade the senses of the sleeping, weigh down and oppress, intoxicate and perplex. Two hundred years later, the Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus describes the notturne larvae as a disease of the imagination that transmit passionate fancies from the mind of one person to another. Unaware, the logic of the imagination is perhaps infested by incubi and succubi: we don’t know why we want what we want, we can’t see, not exactly, what we make, we clothe ourselves in personas, or other garb, project into distant figures so that we can, as one of the film’s three female graces says, find ‘a way of thinking next to thinking’. Or, as yet another of the three women (the artist herself, Rosalind, or Rose, but not sick, Rosie) hints at an artist’s desire ‘to catch the work unawares…just to see what it’s doing, to see it’.

To see it, to see her, him, the artist, the artwork, its proxies, is no easy task, and ‘it helps to think together’, says the woman who opens and closes the film. She is the artist Elena Narbutaitė, a regular collaborator of Nashashibi’s, who has dark curly hair, like Nashashibi, and blue eyes, like the sculptor Marie Lund, both of whom also feature in the film (the trio of graces). The three supplant each other in spoken and visual narratives at various junctures: friendship provides the ultimate gift of subtle distance and transformation so difficult to find alone in the studio.

A woman as a woman as a woman as an artist as an artist as an artist, not quite sure what to look at, not quite sure where the real story lies, if story is the right word at all (it’s not). ‘I found small Rosie in the magazine, but the page was coming from somewhere else’, Elena speaks to no one and everyone, at the outset of the film, sitting in bed leafing through the magazine that ultimately produces the worm. She means, perhaps, what seems to be a black-and-white photocopy from another source stuck between the pages and featuring a woman who we later recognise resembles Nashashibi. But the following pages show roses, too, bright red and white, thriving. ‘And before that I remember seeing Marie at the window in the kitchen’, Elena continues, ‘both not quite themselves and just exactly like they are’.

As the film elapses we see Marie polishing her curved, shining sculptures; Elena beholding them installed in a gallery; Rosalind in her studio (as her son gives a manic tour of new paintings, appropriating the role of the artist with her as his assistant); Elena dancing in an empty space as music pulses in the air (first The Sisters of Mercy and later, Britten); and finally Marie and Rosalind sitting at a table as Elena recites Blake’s poem. At the tangled heart of The Invisible Worm, we see that networks of friends and makers can be resilient tools for thinking with and against the invisible worm, which straddles micro and macro universes – from the studio, filled with encrusted paint tubes, to the heart of the state. ‘His dark secret love / Does thy life destroy’, warns the speaker of ‘The Sick Rose’, describing the invisible worm, but it need not be so. The dark secret is singularity, and it will eat you from the inside until you droop and wilt and fade and disintegrate, dust to dust. This is why artists work every day to make the invisible visible, and truly, it helps to think together, often seems there is no other choice.

1 Michael Srigley, ‘The Sickness of Blake’s Rose’, Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, vol. 26 no.1 (Summer 1992), pp. 4-8.

Emily LaBarge is a Canadian writer living in London. Her essays and criticism have appeared in Granta, the London Review of Books, Artforum, mousse, Bookforum, Frieze, and The Paris Review, among others. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times and 4Columns. Her first book, Dog Days, will be published by Peninsula Press in 2025.